Competing Schools

Surfing and diving deal with gravity differently. A surfer has an exit strategy. Either the plan is to take a wave in all the way to shore, or to exit over the lip to the back of a wave. The power of the wave keeps gravity working, like walking down an escalator. There is an illusory feel of continuous descent. Actually, you are being pushed forward as you are being lifted upward but slipping along the surface. It feels like speed but most of the motion is what is around you. You are reacting to your surroundings in a balancing act.

In diving, the options are more limited. You are the one that is moving. And there is no exit strategy, There is only an entrance strategy. An experienced springboard diver may choose to change tricks midcourse, of course, but the general entry strategy is always the same. Do your best to land in good form without a splash. And don't get hurt.

Ghostsurfers.com's ascent to the top of the web was more like the lift from a dive than a wave. The launch worked out nicely despite its challenges, but after that, there weren't many options. Gravity overpowered momentum. As high as it was, it wasn't high enough. We needed to reach 2 million members to hit net positive for the content explosion that I was looking for.

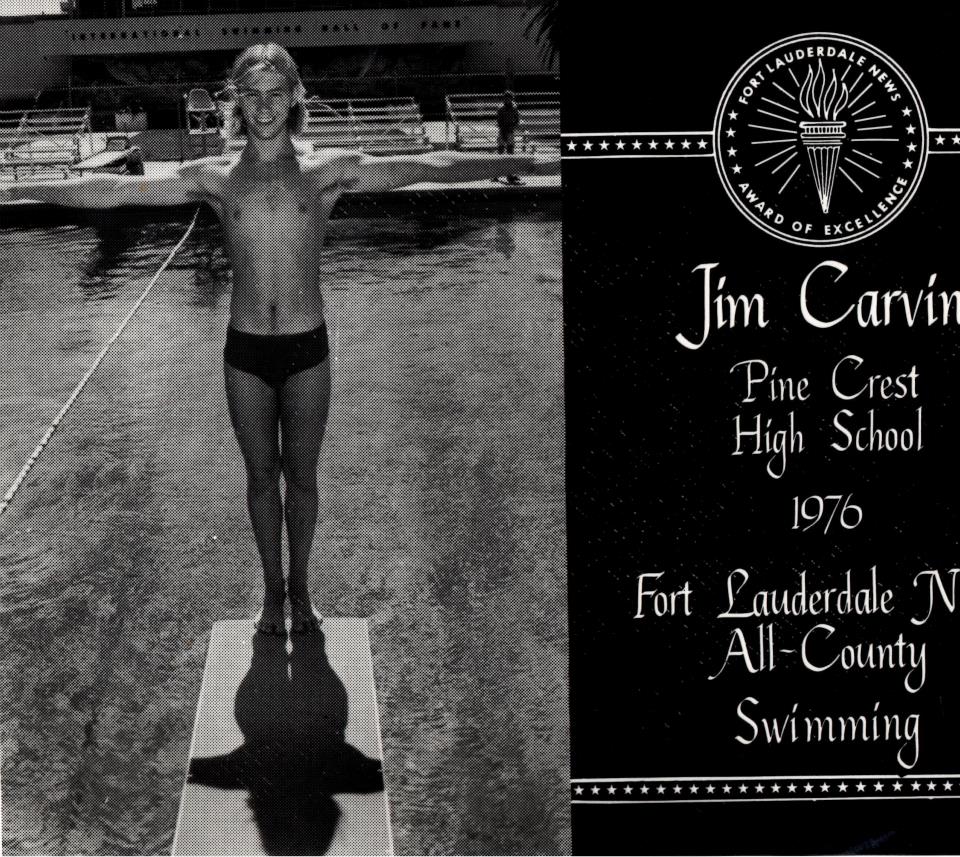

SCHOOL DISTRICT CHAMPION

It didn't happen. Our servers started crashing at around 10,000. By the time we had 20,000 ghostsurfers using the site, we were losing momentum because the servers were too sluggish. People expect technology to work. They laughed at what they called the "world wide wait."

I looked everywhere for the capital needed to buy more servers. I was already investing heavily in site upgrades. I was scrambling to save my dive. My original development company, Advanced Systems Design, decided to end all private sector work when they got the MyFlorida.com contract with Jeb Bush. I considered a company out of India because the price was right, but their work was substandard. I was losing time.

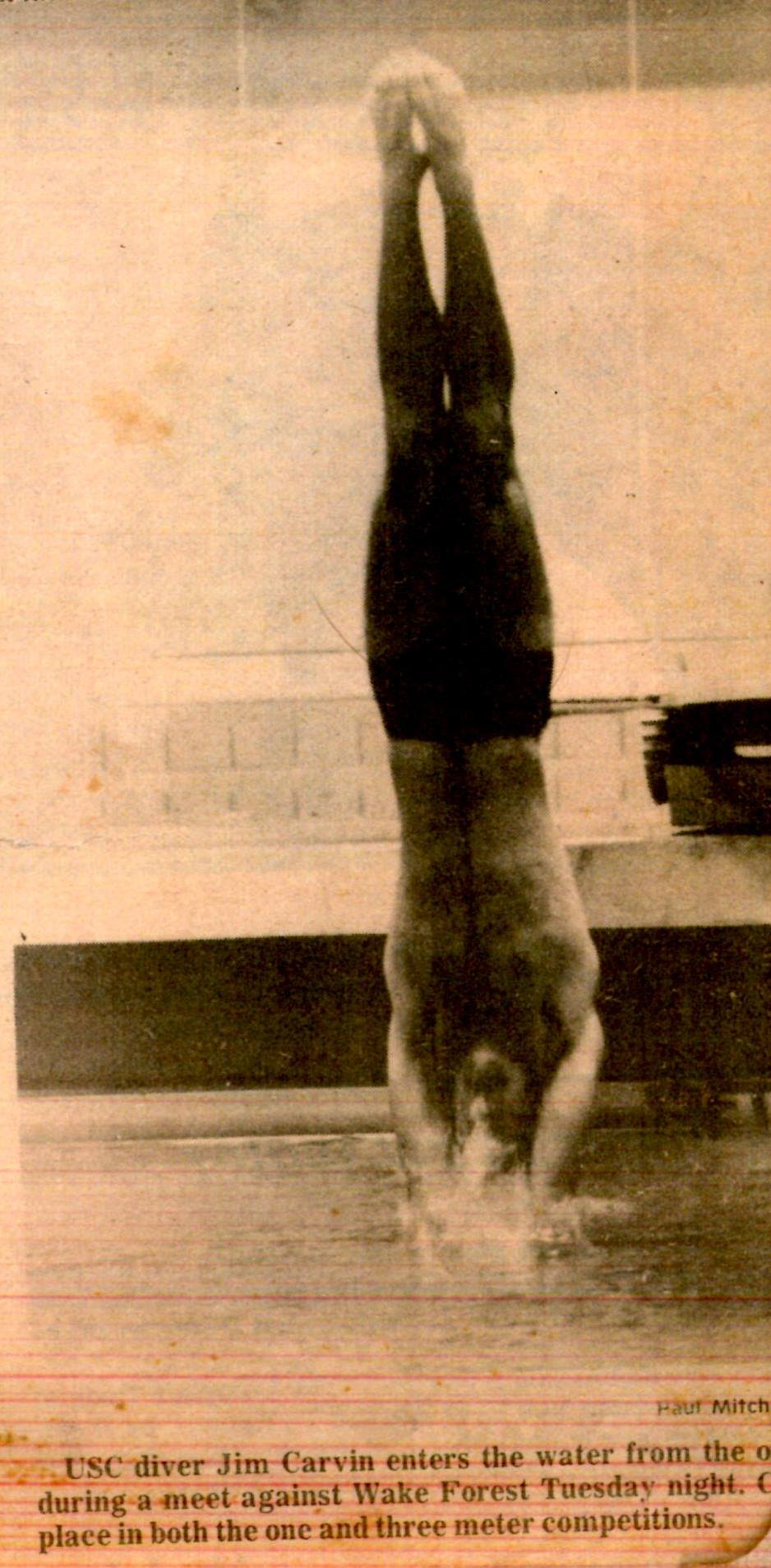

CARVIN NAILS AN INWARD 1 1/2 PIKE ON THE 1 METER

Then a company out of New York came along, I'll refrain from dropping their name for legal reasons. They had been doing work for SesameStreet.com and agreed to work for 5% of our shares.

I thought we might come in for a perfect landing as their work was to cover the entirety of the upgrade. Finally, we would have a fully automated search engine that featured a functional social network for ghosts, who could chat and post messages on forums by category. The entire proposal was laid out meticulously and included several levels of upgrades in a fully automated eCommerce system.

But it was a blind dive. In a blind dive, you enter the water backwards. You can't see where you are in the air. You have to land by feel. The company was in New York. I was in Florida. There was no accountability.

Directing a company blind is not good practice, not that I had a choice at the time. There were no angels knocking on my door with the cash I needed to do otherwise. Even a trip to Sandhill Road in Silicon Valley, the venture capital hub of the world, had turned out to be a complete waste of time and money. I had courted some local Tallahassee entrrepreneurs, as well. But the timing was off. They were all backing out of tech ventures by 2001. There was only one path to take for this dive. And it was backwards.

So down I went, blindly waiting for news daily. And then one day I got a call from the CEO, saying he wanted cash on top of the equity he had previously agreed to. His expenses were greater than he first anticipated. I was afraid to admit how tapped out I was by then. I didn't feel he had a right to ask for more than what we'd agreed to for that phase of the work. I was angered by the delay.

And that's how blind dives work. Sometimes you land them. Sometimes, you don't. I had to sell our car to raise the cash he was asking for. Reluctantly, I did pay him. And then, in time, the work was completed and was pretty good. The relationship, however, was far from over. I now had a business partner with a minority stake. No problem with that. But his way of thinking and doing things was very different than my own.

Never again, will I partner with someone who does not share my vision. Partnership courtship should never be rushed. Decisions made in desperation are seldom good ones. Negotiate from strength. Know your landing.

Naturally. But of course, that advice is for those still contemplating their launch. In mid-air, the decision process is very different. Either your momentum is sufficient for the dive or it isn't.

I wasn't the best diver there ever was. There were others who could do 4 1/2 somersaults in the air. Me, I could barely do 3 1/2. I lacked the fast twitch muscles necessary to do some of today's power dives. For my day, I was very good though. I dove against Greg Louganis and Bruce Kimball. I attended Kimball's dad's summer diving camp in Brandon, Florida two years in a row. I was coached by all the best divers in the world.

Different Disciplines

There are different schools of thought about how to go about business. We all agree that it takes a lot of discipline. But some people breeze through with little apparent effort, while others stress and struggle the whole way.

There are also competing schools of thinking about discipline. How much of it is fun, and how much of it is work? Who are our coaches? What do they say?

Kimball's camp had a ten meter platform tower. I lacked experience from that height. In fact, I had such a fear of heights that I had to stand in the center of the platform away from the edges. It was a radical built-in life preservation mechanism - part of my design.

Not all had the same acrophobic tendency I had. Donny Crane didn't have it. He goofed around at any height fearlessly. Dick Kimball didn't have it, even at the age of forty. He'd hoist a trampoline to the top of the platform, jump down onto it from a twelve foot ladder, and do 5 1/2 somersaults without getting hurt.

That doesn't mean he was fearless. I imagine he did land badly a few times. But he had a disciplinary philosophy that drove him. He was an overcomer. If you wipe out, think about what happened. Get up and try again as soon as possible. Immediately, if you can. He knew what failure could do to people.

Kimball's teaching on this was clear the day he taught his daughter a back 2 1/2 from that same ten meter platform. I was right behind Vicki Kimball, standing fearfully at the center of it, the next diver behind her, preparing to learn the same dive. From my viewpoint, we were looking at one another face to face as she stood backwards on the edge of the tower. Ladies first?

It was her first attempt at the blind dive, just as it would be mine. She stood silently in thought for more than a minute, her heels overhanging the edge, arms out, preparing to swing, jump, and flip backwards with all her strength. Finally, she did it. Up she went, knees leaping up and beyond where her head had been a moment before. I saw her grab them and flip once but I couldn't see the rest from where I was standing. I had to listen.

Pop! It was like the sound of a gunshot. She landed flat on her stomach, a perfect 2 3/4 somersault - a whipping bellyflop. There could be nothing more painful.

Dick had been standing by the poolside. When learning a blind dive, your coach has to call you out of the spin. By stretching out and reaching for the water that you can't yet see, you can stop the rapid spin you've maintained while tucked up. If you do it right, stretching out, you can slip into the water without a splash in a 31 mile per hour descending handstand. But if you're too slow to respond to the call out, maybe panicking, you'll pass vertical. A small pass and the tops of your feet will slap hard. A long pass and your legs will take a beating. A very long pass, and you'll get what happened to Vicki.

The wind was knocked out of her. Her father consoled her but urged her to climb back up and do it again. My turn was next. I learned from Vicki's mistake and managed without much overage or pain. And when I climbed back up, she was there in front of me again. The Kimballs were from Michigan. Staring at her now as before, her formerly pale skin was black and blue from head to toe. Her father wouldn't let her back out. He knew she'd be too spooked to ever learn the dive if she didn't learn it that very day.

Then came more bad news. Another try, same results - same loud, flat, body-clapping pop. More talk down below. Then I did mine and we were all up again for a third round. Her third try was about the same as my first. She survived. As for me, I didn't just learn a new dive. I had a lesson in tough love. It must have torn him up to see his daughter that way, knowing he had urged it all on. He must have felt her pain even more than I did, maybe more than she did. Others might call it child abuse. There are different schools of thought.

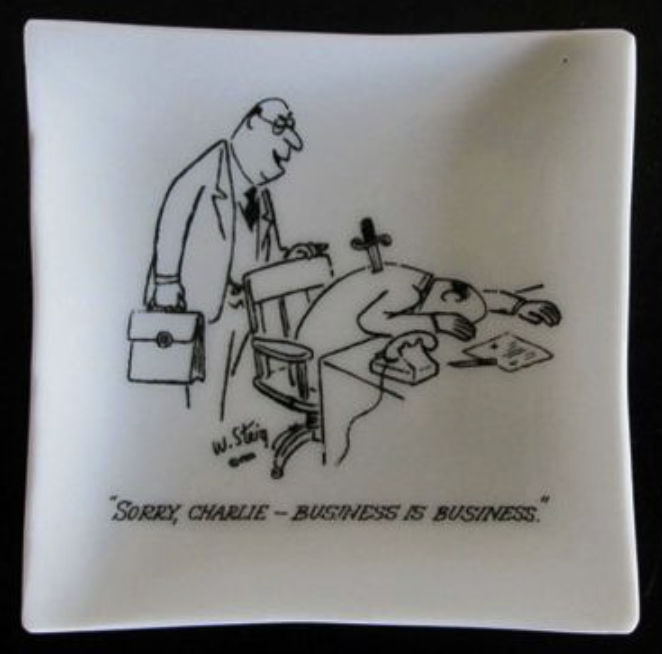

THE ASHTRAY CARVIN INHERITED FROM HIS FATHER'S DESK

The business world has many schools of thought. It's not just that it's tough. Sometimes it is. It's the different philosophies.

In my way of thinking, all people mattered. Everyone in the world had a share in what I was doing, If I succeeded, it would eventually affect everyone. My own overriding thought about going into business was all about what might accomplish the most good for the most people. I wasn't just thinking about the stakeholders that were instrumental in the business. I wasn't just thinking about the ghostsurfers either. I was thinking about everyone. The better search engine I wanted was for everyone. It was for the historical record of the whole world.

My own father's philosophy of business was much more common. You go into business to make money. Your business partners are in it for the same reason - money. What they do with their money is their own business. And if you have investors, you have an obligation to do one thing - earn them top dollar on their shares.

Charlie Carvin was a simple man in that way. And since most do business with that philosophy, the business world can be pretty rough. He reminded me of that with the ashtray he always kept on his desk. Business ethics was something you claimed to have so the public would think well of you. Outside of that, business involves an agreement. Since we enter into agreements voluntarily, they must be inherently ethical.

The Sesame Street coding group finally produced a true search engine per my specifications, but there was much they didn't tell me. They didn't tell me Sesame Street had backed out on them. They didn't tell me that they had started to outsource their work when they could no longer afford their own employees. They didn't tell me that they had built a back door to our servers and hired programmers from Russia to build our forums and the framework for our social network 102.

Worst of all, they didn't tell me that they hadn't paid the Russians what they were owed for their work. And by the time I found that out the hard way, they forgot to mention that they had declared their company bankrupt. Perhaps, if the Russians had understood that I was a creditor who'd done my own part in full, just like they were, they wouldn't have taken out a vendetta on me. But someone named Anatoly was asking for his money in exchange for our data.

That's right. Through the backdoor he built, someone calling himself Anatoly was able to access the server. He also learned all about our back up system. Forensics showed he first took the data and next wiped each backup clean. We rotated eight back ups in those days. He imploded them incrementally, one day at a time, so we could never recover. By the time the site went down on the eighth day, the Sesame Street people weren't answering phone calls. My wife was furious that I had sold the car for this. It was a total wipe out and we were flat broke, our dreams dashed to pieces. Pop! And then I was back to the drawing board. Sure, it's painful but you can't let fear paralyze you. The faster you get back up to try again, learning from your mistakes, the better ...